Appendix D: Research Methodology

Introduction

1.1 A summary of the approach taken and reasons for the methods used appears in Chapter 1 of this report. The purpose of this appendix is to provide a fuller technical explanation of the research methodology.

1.2 As stated in Chapter 1 LSET involves a complex set of research issues. It was necessary to gather data on the experiences and perceptions of those involved in delivering LSET and those benefitting from it, and of other interested persons including clients/consumers. This data included views of the current system and expectations of and desires for the future. An iterative approach was adopted which involved returning to issues as they became better defined. Because much of the data was to be based on perceptions and experiences it was necessary to triangulate information from different data sources so as to increase assurances as to the consistency and reliability of the findings. The LETR research phase uses both qualitative and quantitative data to carry out these tasks. The research team’s empirical approach was fourfold: (i) meta-analysis of existing research data and other material, such as existing competence statements, where available; (ii) collection of original qualitative research from interviews and focus groups; (iii) collection of original quantitative data, primarily from online surveys, and (iv) collection of further qualitative data from a range of stakeholder engagement activities.

1.3 The LETR research phase has adopted a dual approach adopting full qualitative data enquiry as the primary method, aiming to understand the complexity of the context, content and systems, and with quantitative research data to provide evidence on the strength of different views regarding current context and possible changes. Evaluation and assessment of LSET required evidence based upon the experience and judgement of stakeholders and participants in the provision and consumption of legal education and legal services. While some of these data were captured through questionnaire-based attitudinal surveys, qualitative methods were designed to discover meaning through fine attention to content, so interviews and focus groups allowed for a wider range of responses, with richer description and deeper analysis of the phenomena than would have been achieved by quantitative research.

Ethical issues

1.4 Research ethics approval for the empirical elements of the work was obtained through the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies from the School of Advanced Study of the University of London on behalf of the consortium of institutions undertaking the research.

1.5 Research ethics require that informed consent is obtained from interviewees and focus group members, and that appropriate agreements are in place as regards confidentiality and the use of data obtained from participants. For reasons of confidentiality, individual interviewees or focus group members are not identified, neither are interest groups, educational institutions, firms, employers or chambers without their explicit consent. Where consent has been obtained, their details appear in the list of participants in Appendix A.

1.6 The stakeholder responses to Discussion Papers or other submissions to the LETR research team are identified in common with the usual practice of public consultations. The research team were aware of the sensitivity of some of the issues. Accordingly respondents were permitted to submit either anonymous public responses, or confidential responses, to the research team (though in the event very few respondents selected either of these options).

1.7 One consequence of data confidentiality is that the qualitative data is represented by summaries and selected quotations, rather than by complete transcripts, which might lead to identification of individuals or organisations from elements of the discussion. Given the many pages of transcript, this approach also produces something more readable. Quoted comments are selected for a number of possible reasons as indicated in the text. In some cases these are reported as illustrative of a preponderance of views, in others as illustrative of a range of views, or as demonstrating a divergence between different professions or groups. Often a quoted comment will better express a view or theme or demonstrate the strength of feeling behind such a view.

Research activities undertaken

1.8 Initial research tasks were revised and adapted as the investigation progressed along with additional research activities. Ultimately a larger number (see table D.1) of interviews and focus groups were carried out than originally planned in order to access a wide range of participants, both by demographic background and by location. In total, 42 interviews were carried out by the LETR research team with 56 individuals and 39 focus groups were held. In addition, Professor Richard Susskind undertook a further series of interviews, not included in the LETR research team’s figures, which contributed to his briefing paper Provocations and Perspectives.[1] The research activities undertaken were as follows:

- Interviews with City law firms;

- Focus groups with Legal Education and Training Group members and local Law Society education committees;

- Interviews with senior lawyers;

- Exploration of the future role of information technology;

- The new research collection of information for Solicitors and their Skills study;

- Analysis of LSB commissioned Legal Services Benchmarking Survey data;

- Research interviews with Alternative Business Structures;

- A series of focus groups and interviews on the skills required of individual lawyers and on mobility in the professions;

- Online survey examining possible LSET frameworks;

- Additional focus groups and interviews with regulators and targeted groups;

- Survey with Will Writers;

- Survey with HEI Careers Advisers.

1.9 Table D.1, below, provides an overview of the numbers of individuals and groups that were consulted through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and surveys.

Table D.1 LETR research consultations overview

|

Overview of number and type of respondents |

|||||

| Focus group | Focus group (number of groups) - treated as 3+ people[2] | Depth interview (number of respondents) - treated as 1-2 people | Main quantitative survey (number of respondents) | Careers Adviser survey (number of respondents) | Will Writers survey (number of respondents) |

| Regulators | |||||

| Domestic legal sector regulators | Meetings were held with 6 regulators in some form. Sometimes this was a meeting/interview, on other occasions regulators participated in focus groups | N/a | N/a | ||

| Other regulators | 4 | N/a | N/a | ||

| HEI based respondents | |||||

| Academics[3] | No of dedicated focus groups[4]:9 Number of respondents in total: 39 |

14 | 84 | N/a | N/a |

| Careers advisers | No of dedicated focus groups: 0 Number of respondents in total: 1 |

19 | N/a | ||

| Librarians | No of dedicated focus groups: 1 Number of respondents in total: 4 |

N/a | N/a | ||

| Legal sector professionals | |||||

| Solicitors (including trainees)[5] | No of dedicated focus groups:11 Number of respondents in total : 93 |

13 | 326 | N/a | N/a |

| Barristers (including pupils) | No of dedicated focus groups: 4 Number of respondents in total 39 |

4 | 312 | N/a | N/a |

| CILEx members (including trainees) | No of dedicated focus groups: 1 Number of respondents in total 9 |

5 | 162 | N/a | N/a |

| Paralegals[6] | No of dedicated focus groups: 0 Number of respondents in total 5 |

5 | 34 (+ 2 claims managers) | N/a | N/a |

| IP attorneys | No of dedicated focus groups: 1 Number of respondents in total 10 (inc regulator) |

0 | 1 | N/a | N/a |

| Notaries | 2 (regulator) | 43 | N/a | N/a | |

| Will writers | 2 | N/a | 139 (28 pilot; 111 final) | ||

| Licensed conveyancers | No of dedicated focus groups: 1 Number of respondents in total 5 (inc regulator) |

0 | N/a | N/a | |

| Costs lawyers | 2 (regulator) | 3 | N/a | N/a | |

| Students[7] | |||||

| Foundation degree | No of dedicated focus groups: 1 Number of respondents in total: 16 |

0 | 67 students | N/a | N/a |

| QLD | No of dedicated focus groups: 1 Number of respondents in total: 13 |

3 | N/a | N/a | |

| LPC | No of dedicated focus groups:1 Number of respondents in total: 9 |

1 | N/a | N/a | |

| BPTC | No of dedicated focus groups: 0 Number of respondents in total: 4 |

0 | N/a | N/a | |

| GDL[8] | No of dedicated focus groups:0 Number of respondents in total 0 |

0 | N/a | N/a | |

| LLM | No of dedicated focus groups:0 Number of respondents in total : 1 |

0 | N/a | N/a | |

| Other stakeholders | 87 | N/a | N/a | ||

| ABS | 3 | N/a | N/a | ||

| Judges | No of dedicated focus groups: 1 No of respondents in total: 3 |

5 | N/a | N/a | |

| TOTAL | No of focus groups: 39 No of respondents in total: 251 |

56 | 1128 | 19 | 139 |

Note: Numbers do not include large open events such as those hosted by the LSB or the Nottingham Law School debate, conferences, symposium discussions. Nor does it include the 18 respondents to the Young Lawyers Forum; the Solicitors and their Skills participants or spontaneous submission to the LETR website. BDRC Continental consumer data is also treated separately (see Chapter 1).

1.10 ‘Interview’ is defined as a meeting with one or two people. Many were face to face although for logistical reasons some were carried out by telephone or by emailed response to questions.

1.11 Interviews and focus groups were semi-structured, involving an initial series of prompt questions. Prompt questions were derived from the over-arching research questions and adjusted for the group (eg, students, academics, practitioners, regulators) participating. As the context of the research changed (eg, in relation to development of ABSs and the Welsh jurisdiction consultation) and as data gathered from previous groups was analysed, questions for later groups were refined and developed to focus on gaps or matters of particular interest to the research. Participants were also able to raise issues of concern to them within the overall context of the research, even if not specifically addressed in the interview guides.[9] An indicative selection of interview guides appears in Appendix E.

1.12 Processes of selection or invitation to interview and focus group participants are described below in relation to each research activity. Selection and invitation was carried out, in large part, ‘purposively’ in order to gain access to a particular group or geographical region. In some cases additional participants were recruited by ‘snowball sampling’ in which existing participants suggested or invited others.

1.13 Unless otherwise stated, the interviews or group discussions were transcribed (or in cases where recording was not possible, noted), and fed into the thematic analysis of qualitative data (see below). The emerging themes were initially set by readers blind to the aims of the project arising out of initial focus groups and interviews. These themes were followed and enhanced in accordance with grounded theory practice as the research progressed.

1.14 A summary of each of the individual research activities is outlined below:

Interviews with City law firms

1.15 A total of three interviews were undertaken with representatives of City law firms about developments in the international legal services market and trans-national entities as well as issues of training and development for global practice. These participants were initially suggested by the Co-Chairs of the CSP as individuals with a good grasp of the issues and important experience to impart. Respondents also discussed bespoke LPCs and in-house training structures, international qualifications, issues of outsourcing, technology and specialisation and diversity and social mobility in recruitment.

Focus groups with Legal Education and Training Group members and local Law Society education committees

1.16 Two focus groups were carried out with members of the Legal Education Training Group.[10] Participants in the LETG focus groups included representatives of both City and large national firms and a small practice. Practitioners were invited to discuss the changing regulatory landscape, both generally and by reference to specific prompts about, eg, ABSs, outsourcing, the growth of the unregulated sector, and implications of technology.

1.17 A number of local law societies were selected for approach by reference to location and situation (eg, city, rural area). Four focus groups were held. Participants in local law society focus groups also discussed the different stages of LSET for solicitors and management and supervision of paralegals.

Interviews with senior lawyers

1.18 A total of four specific depth interviews were undertaken with senior lawyers from the Bar, legal aid and national law firm practice examining developments in the international legal services market and trans-national entities. Respondents were approached as a result of discussions at focus groups with the Legal Education and Training Group, suggestions by the Co-Chairs of the CSP and balanced with interviewees with different backgrounds and areas of work. This activity was developed to ensure coverage of different sectors and professional groups and there is some overlap of coverage with other research items and events. Interviewees were selected purposively as having a particular expertise and perspective on topics such as international practice or legal aid practice. This material was substantially supplemented by work with other senior lawyers, regulators and groups reported below as additional focus groups and interviews.

Exploration of the future role of information technology

1.19 A series of interviews about the future role of information technology in legal practice and LSET was undertaken by Prof Richard Susskind, and contributed to his briefing paper Provocations and Perspectives.[11]

1.20 Professor Susskind drew on four interviews conducted specifically for LETR, a series of interviews across the profession in which he raised LETR, as well as his own on-going research and consultancy activities. These included two extended interviews with experts about professions outside law, six confidential discussions with leading practitioners (including General Counsel and senior partners in major firms) and discussions with academics and students at three seminars (one in England, one in Holland, and one in the US). He also drew on his on-going collaborative research with Daniel Susskind and 50 face-to-face, interviews carried out last year across the professions, and on insights gained during 2012 from five client consulting projects (three leading law firms and two in-house legal departments).

1.21 Themes discussed in interviews included how professional and legal services will be delivered in the future; the remit of law schools and universities in preparing individuals to practise in the law and other professions; the needs and wants of in-house lawyers and other informed commercial clients in the purchase of legal services; the educational value of work allocated to young lawyers; the implications of technology for both practice and education; the place of theory in legal and professional education and the relationship between practitioners and academics; and new skills needed by tomorrow’s lawyers.

New research collection of information for ‘Solicitors and their Skills’ study

1.22 This research collected data from practising solicitors i in order to determine how they were spending their time on different tasks and skills. It was then possible to compare these findings with the research project originally conducted in 1990 in preparation for the (then) new LPC.

1.23 Five days of data were collected from each of 34 practising solicitors across a range of firms. These findings were compared and analysed with each other and against the original work, providing an empirical basis for assessing changes in work of solicitors, and any effects of the increasing influence of ICT, etc. Firms were approached by e-mail from a list of contacts generated from individuals who had been involved in previous LETR interviews and focus groups. They were given a period of over six weeks, and several e-mail reminders to return completed timesheets. Some firms subsequently declined to be involved, others did not respond. Those that did were encouraged to gather responses from a range of fee-earners. A detailed briefing document (Appendix E) was sent to firm contacts for circulation to volunteers and results sent by participants directly to the research team.

1.24 The six firms involved range from small regional legal aid firms, to mid-sized firms doing a variety of criminal, civil and commercial work, to large City firms.[12] Individual respondents had between 0 and 26 years post qualification experience, with an average of 4.6 years.

Analysis of LSB commissioned Legal Services Benchmarking Survey data

1.25 The original research plan included a survey of legal services consumers to explore trends and changes in consumers’ needs and requirements. Following discussions with the LSB and Legal Services Consumer Panel, it was decided that it would be more beneficial to access data from the 2012 Legal Services Benchmarking Survey rather than duplicate effort.

1.26 The survey was commissioned by the Legal Services Board in 2011 and was undertaken by BDRC Continental, a research consultancy. BDRC contacted a representative sample of adults via an online questionnaire. The questionnaire covered a broad range of legal problems from transactional consumer problems to employment rights issues. A total of 4,017 respondents completed the survey.

1.27 The study covered many aspects of the journey individual consumers take, from first identifying that they have a legal need, to the action they take to address this need, ending with the legal service provider used. Each element of the consumer journey was investigated in detail to explore how choices were made, satisfaction with the process chosen and whether the choices made led to a resolution of the problem. Survey respondents were presented with a list of 28 descriptors of potential legal issues. The survey explored up to three legal needs experienced by each of the 4,017 respondents – over 9,800 individual needs in total.

1.28 For the purposes of this report, the results of the two largest groups of service providers (solicitors and CABx advisers) in the Legal Service Board/BRDC dataset were analysed, and contrasted with the average results for all providers. The aspects selected for particular analysis, as being under-represented in the main data corpus, were the questions “How satisfied were you that your service provider clearly explained the service being provided?” and “How satisfied were you that your service provider treated you as an individual?”

Research interviews with Alternative Business Structures

1.29 Interviews with the first 20 Alternative Business Structures (ABS), to be authorised were planned in order to identify any novel issues in education and training emerging from a new model of legal service delivery. However newly approved ABSs were problematic to engage with. They were by their nature new enterprises focusing on establishing their businesses. Some ABSs contacted advised that they did not have relevant information at this stage. Nevertheless, interviews were undertaken with two new ABSs and one further ABS provided a written response to questions provided by the LETR research team.

1.30 Themes arising included rationale for the choice of regulator, implications of ABS status and strategies for education within the ABS. The research team also gained insights into the market that might develop through its interviews with organisations using similar business models.

A series of focus groups and interviews on the skills required of individual lawyers and on mobility in the professions

1.31 It proved possible to generate a detailed benchmark list of skills, knowledge and attributes for practice from desk-based analysis of a number of existing competence frameworks which allowed work on this topic to be accelerated.[13]

1.32 A total of 16 focus groups and nine interviews involving academics, students/trainees and practitioners were arranged. Academics and student meetings were arranged around institutions by reference to geographical spread and type of institution.[14] Volunteers were then sought from that institution. Focus groups with local practitioners were arranged, as stated above, by asking local law society, Bar circuit and CILEx branches to circulate their members and by direct invitation to firms and chambers in the vicinity. A small number of supplementary interviews and written responses accommodated some respondents who had wished to participate in these focus groups but had been unable to do so.

1.33 Participants in this group of focus groups were invited specifically to consider the key skills, knowledge and attitudes required for practice. They also discussed the extent to which those attributes were delivered by existing LSET systems, including CPD. Participants also discussed regulatory constraints and issues of mobility, equality and diversity. Student participants in particular showed a keen interest in progression routes and in the information available to them about entry into the professions.

1.34 Participants in Wales additionally discussed the emergence of a distinct Welsh law and its possible implications for practice and for education. Issues that had been identified by participants in Wales were then raised with participants in England.

Online survey examining possible LSET frameworks

1.35 The primary source of quantitative data for this phase was the LETR online survey. Between 30 April and 16 August 2012, the LETR research team conducted a large-scale open survey of individuals with an interest in matters relating to legal education. The survey was designed by the research team using the proprietary online research software SurveyMonkey, and promoted through the LETR website, by the commissioning regulators; both social and print media and to organisations represented in the CSP. Participants in focus groups and interviews taking place during the survey period were also invited to participate and to circulate details of the survey to colleagues and members. Shortly before closure of the survey, it became apparent to the research team that solicitors were underrepresented in responses and the SRA issued a reminder on 7 August. By the closing date the survey achieved a broad and statistically robust sample of 1,128 persons.

1.36 The survey was designed to obtain both demographic and quantitative attitudinal data from respondents on a range of issues, including the necessary knowledge, skills and attributes required of legal service providers.

1.37 The survey was piloted on selected legally qualified academics and informed members of the public. These tests addressed issues of length, cogency and question design, and testers were asked to make comments regarding any aspect of their experience completing the survey. Some changes were made to multiple choice questions as a result of these tests, including the addition of a ‘N/A’ response option to some forced choice questions.

1.38 The survey consisted in large part of questions in the form of statements, which were based on ideas drawn from materials produced by the Legal Services Board, frontline regulators, respondents who had participated in earlier LETR empirical research, leading academics, and others, to capture a number of issues relevant to the research questions. A number of the attitudinal questions linked directly to issues explored in Discussion Paper 01/2012, and thus provided data that could be contrasted to the formal stakeholder responses.

1.39 There are necessarily some limitations in designing a questionnaire of this nature. For example, respondents could only answer as a member of a single occupational group, so if for example an individual were qualified and practising as both a solicitor and a notary public, then he or she could only have answered questions as one or the other, without completing the survey twice.

1.40 Respondents were invited to indicate the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with a given statement using a Likert scale ranging from strongly positive to strongly negative. The use of forced choice questions does not permit detailed nuancing of responses, but it can provide clarity in terms of strength of particular views experiences.

1.41 The survey also gave respondents scope to add free text comments, which were separately analysed as part of the qualitative data. This allowed respondents to express more nuanced responses and to comment on particular questions or on the survey itself. Some responded at length. It was clear that a few respondents feared that the survey had been designed to create an appearance of a false consensus or to justify a series of pre-determined changes directed at limiting professional autonomy, de-skilling practitioners, promoting competition at the expense of quality, or other similar concerns. This was not the case, although the research team carefully evaluated such comments in the course of analysis and have acknowledged issues arising from survey design in the report.

Additional focus groups and interviews with regulators and targeted groups

1.42 Five focus groups were held with in-house lawyers (three in the private sector and two in the public sector) who provided informed insight as purchasers of legal services. Participants included solicitors and barristers, trainees and pupils. In the private sector a range of commercial organisations was represented. In this context themes discussed included use of external lawyers (and alternative service providers) and evaluation of the service provided. These participants also discussed themes relating to their own education and training and the extent to which in-house practice might be represented in LSET.

1.43 As work progressed, the research team convened a further 23 interviews and 12 focus groups with groups who had not yet been represented. This included meetings with regulators and representatives of the smaller professions, organised through their regulators; with regulators outside the domestic sector and with paralegal organisations (two focus groups and nine interviews). These focused on the interrelationship between education, standards and regulation; the appropriate levels and targets of regulation and challenges to the sector (such as outsourcing, ABSs). Respondents were asked to identify aspects of LSET or regulation used in their profession which could be of wider application.

1.44 Three interviews were carried out with employment advisers in the unregulated sector on their work and their training models.

1.45 Other interviews and focus groups in this category included:

- academics, library and research professionals and others who discussed aspects of particular LSET models (eight interviews and three focus groups);

- young lawyer and diversity groups (five focus groups) who discussed issues of mobility, entry, progression and information;

- CILEx members (three interviews and one focus group) discussing their experiences of the CILEx route(s) in particular;

- members of the judiciary (one focus group) who discussed standards in advocacy performance.

1.46 Obtaining sufficient access to diversity groups proved problematic and the research was supplemented by the Equality and Diversity Advisory Group and the Young Lawyers Forum (see below).

Survey of will writers

1.47 A survey of will writers was piloted in paper form at the Institute of Professional Willwriters Annual Conference in February 2012, and subsequently circulated in electronic form to the wider membership of the Society of Will Writers and the Institute of Professional Willwriters by gatekeepers at those organisations who sent the link to their membership. The survey sought to examine attitudes amongst will writers to the move to make will writing a reserved activity. It also canvassed opinion on the form that any regulation should take. Whether there ought to be a prior educational standard for will writers and the adequacy of existing continuing professional development were also examined.

1.48 A total of 139 responses were received. No claims are made as to the representativeness of this data, and it should particularly be noted that responses do not include will writers operating outside the voluntary standards imposed by membership of these associations.

Online survey of HEI careers advisers

1.49 Between January and March 2012, an online survey was conducted among law careers advisers in higher education. Careers advisers were selected because of their role as knowledgeable intermediaries between the legal services market and students, and hence as a relatively impartial source of triangulation for a range of issues being explored through the qualitative and quantitative data. They were asked in the survey about their perceptions of the skills, knowledge and behaviours sought by recruiters and the deficiencies in new recruits which appeared to be of most concern to prospective employers. Respondents also provided data on extra-curricular activities and the ‘social capital’ sought by employers; on prospective changes in employers’ preferences and possible trends in relation to the CILEx graduate entry programme.

1.50 The survey was facilitated by convenors of an online discussion list for HEI careers advisers with an interest in the legal profession, who circulated the link to the survey directly to members. It obtained 19 responses from a cross-section of pre-1992 and post-1992 institutions (out of a possible 124):

- Oxbridge – 1;

- Russell Group – 5;

- Private HEI providers – 7;[15]

- Post 1992 – 4;

- Pre 1992 – 1;

- Educational charity – 1.

Analysis of submissions to the research team

1.51 In addition to solicited submissions in response to specific LETR publications, the project website also invited interested persons to make submissions on any issue at any time up to 28 September 2012. By that closing date six such submissions had been received. All responses to Discussion Papers and unsolicited submissions have been incorporated into the main NVivo database and analysed in conjunction with the main corpus of qualitative data in order to reduce any stakeholder bias involved.

Young Lawyers Forum

1.52 The Young Lawyers Forum was convened towards the end of the research to ensure that a cross-section of young lawyers was engaged in the final iterative stage of research, and to test a number of ideas for the future that had emerged from the data. A group of 18 volunteers was identified, including some who had participated in earlier focus groups, and through young lawyers’ organisations. The group represented the Bar, CILEx, solicitors and those working as paralegals. Constraints of travel and timing meant that the discussions took place in three separate events, and by a combination of face to face meeting and telephone conference. Some of the volunteers were not able to participate directly in any of the events but commented at a later stage. Participants discussed technology and the future of legal practice as well as a number of issues surrounding the current LSET system: entry, bottlenecks, vocational education; supervised practice; specialist licensure and diversity. Notes of discussions were combined by members of the research team into a report which was circulated in draft amongst members of the group for additional comment and amendment.

1.53 The remainder of this Appendix provides a general overview of the approaches adopted in respect of analysis of the main elements of empirical research.

Analysis of qualitative data

1.54 LETR adopted ‘thematic analysis’, a form of grounded theory, to analyse qualitative data, such as interviews, group discussions, or written submissions. Grounded theory starts with data collection, and then works backwards to the questions and answers. Once the data has been gathered, it is organised into manageable parts, from which a hypothesis is developed, or on which a theory is based.

1.55 Through a process of reading and re-reading transcripts, then identifying, comparing and contrasting relevant components, thematic analysis aims to identify themes within the data, and has become the most commonly used analytic method for qualitative research involving interviews. Ezzy (2002:87) suggests two reasons for this approach, first, it allows for the emergence of themes during the process of data collection and analysis (rather than the researcher setting the themes at the outset, by predefining a hypothesis for example) and second, it makes it possible for emerging themes to guide the remaining data collection.

1.56 In the course of this project, wherever possible the interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed soon after they took place, and in total rather than quoting selectively. This was both to avoid accidental bias, and because it was helpful to the iterative process of refining interview and focus group questions if the research team could feed points of interest back into their data collection as the work progressed. If one group of respondents raised a particular issue, it could be put to other respondents to discover whether it was particular to that first group, or if it was of wider relevance, thus aiding the researchers in their efforts to define the boundaries of the issues in question.

1.57 In thematic analysis, important points in the data are identified and tagged with a series of codes, which emerge from the text. The codes are then arranged – thematically – with similar concepts grouped into categories in order to make explicit the key issues and arguments surrounding the matter under investigation.

1.58 To preclude the possibility of bias, and ensure that the analysis was truly ‘grounded’, the research team first used the assistance of appropriately supervised psychology students from Brunel University on a work placement at University College Medical School, and asked them to closely read the transcripts of two early focus group discussions, appending what they perceived to be the important points with thematic codes of their choosing. This activity provided a helpful beginning benchmark and means of cross-checking the developing themes.

1.59 The research team amassed a large amount of qualitative data; with 190 items (including comments attached to two open-ended questions in the online survey and responses to discussion papers). A data set of this size is too unwieldy to code reliably unaided, so the research team used NVivo, a qualitative data analysis computer software package, developed by QSR International for use by researchers working with volumes of rich, text-based data. NVivo facilitates the methods of thematic analysis, allowing researchers to tag data with codes that can then be standardised across different texts to draw out relevant concepts. Represented in the NVivo database, the LETR data amounted to in excess of 1200 pages (166MB) of textual information.

1.60 Certain key concerns became evident at a relatively early stage and were common across the legal sector; these were explicitly drawn out and explored with later participants. The research team was able to use briefing papers and discussion papers to raise some of these issues with stakeholders, and invite responses that both clarified details and helped sharpen the conceptual focus, and to provide triangulation of the views emerging from the qualitative sources. In order to gain a broad and textured perspective, interviews and group discussions were continued to a point at which new themes ceased to emerge, indicating that a representative, if not exhaustive, set of data had been collected.

1.61 While standards such as generalisability and reliability are used to judge the quality of quantitative research, qualitative research is not judged by counting responses. A group response from a number of young lawyers may be different from the response of a senior judge. Qualitative research is validated by, for example, prolonged engagement in the issues, understanding the culture and building rapport with participants; giving more weight to widely evidenced data; confirmation by comparison across a range of sources and approaches (‘triangulation’), checking for, recognising and clarifying researcher bias; following up and exploring surprising findings in the research, as well as testing and discussing preliminary findings with an expert panel (the CSP). The experience and expertise of the research team were also relevant in understanding and identifying the import of the emerging findings.

Analysis of quantitative data

1.62 All quantitative data were analysed to produce a range of primarily descriptive statistics (frequencies and cross-tabulations of variables). The larger data sets were analysed using SPSS, a powerful proprietary software package designed specifically for statistical analysis in the social sciences.

1.63 The primary source of quantitative data was the LETR online survey. LSET reform is a socially complex problem, which takes place in a field where there are multiple stakeholders; there is limited consensus about the legitimacy of stakeholders as problem-solvers; and, in which stakeholders are likely to have different criteria of success. While some had the opportunity to participate in group discussions or interviews, or make submissions through representative groups, and anyone could contact the research team directly, a large-scale online survey was regarded as the most efficient and effective vehicle for involving interested individuals in the research process directly, allowing them the opportunity to make qualitative contributions, but also collecting valuable quantitative data, and biographical information that would allow the research team to compare the experiences of different groups. Individual respondents could therefore choose to participate in the project either by sending in views or information or by being involved in the survey. This provided reassurance in a sector of divided stakeholder interests, as any interested individual was afforded the opportunity to represent their own interests or views.

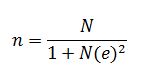

1.64 The online survey, conducted between April and August 2012, generated 1,128 responses. The sample size was assessed against the population of people who might have an informed interest in matters of legal education in England and Wales, to determine whether it was statistically reliable. Yamane (1967:886) provides a simplified formula to calculate an appropriate sample size:

Where n = the number of respondents, N = the population size, and e = margin of error.

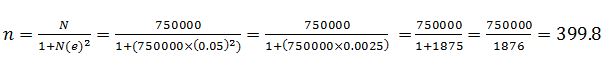

1.65 The first step was thus to determine the population, that is the group of people who might conceivably want to contribute their opinion to the project. The most generous estimates of the size of the legal sector are about 500,000,[16] including a majority of paralegals, some of whom may have no formal legal training. There are also those who do not work in the legal services sector themselves, but maintain an active interest, such as legal academics, law students, people in government or business, and a minority of consumers. To be safe, half again was added to produce a rough estimate of 750,000 as our N. The population of England and Wales is 56.1 million,[17] which means that it was estimated that about 1.3% of the population would have the knowledge and interest to complete the survey. In reality only a minority within the legal sector and a few others would take part; but the purpose of this exercise was to set an upper limit on the number of people who might be considered part of the relevant population, in order to calculate the appropriate size for a statistically reliable sample. Having determined the maximum population that might be eligible to respond to a survey, and settled on the usual social science standard of a 95% confidence level (thereby giving an e figure of 0.05), Yamane’s formula was used to calculate the size of a reliable sample: 399.8.

1.66 The actual sample of 1,128 greatly exceeds this, and can thus be safely treated as reliable for statistical purposes. However, this does not guarantee the representativeness of the sample – ie, that respondents accurately represent a cross-section of the target population. Representativeness depends more on the methodology for sampling and gathering data. In this case, as an online survey was used with a largely self-selecting sample, there are a number of sampling biases which cannot be ruled out and may reduce the representativeness of the data. A number of steps taken to address this limitation and to minimise inadvertent bias in using and interpreting the results of the survey are described below. Specific points about the wording of individual questions, or arising from comparison between the qualitative and the quantitative data, are discussed in the main chapters of the report.

1.67 A substantial amount of demographic data was gathered as part of the survey for purposes of comparison and as a further indicator of the representativeness of the data relative to its target population. These included a total of 29 occupational categories, which given the focus of this project – and the fact that regulation by title is the effective status quo ex ante within the legal sector – was regarded as the most important basis for comparison between different groups within the sample.

Table D.2 Occupational groups responding

|

Occupational Group |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Solicitor (including trainees) |

326 |

28.9 |

| Barrister (including pupils) |

312 |

27.7 |

| CILEx member (including trainee legal executive) |

162 |

14.4 |

| Academic/law teacher/training provider (public sector) |

64 |

5.7 |

| Other interested person |

53 |

4.7 |

| Notary public (including trainees) |

43 |

3.8 |

| Paralegal working in a regulated entity |

24 |

2.1 |

| Academic/law teacher/training provider (private sector) |

17 |

1.5 |

| Law student (BPTC) |

17 |

1.5 |

| Law student (LPC) |

16 |

1.4 |

| Legal support staff (including HR) |

13 |

1.2 |

| Law student (university, undergraduate) |

12 |

1.1 |

| Other paralegal or unregulated provider of legal services |

10 |

0.9 |

| Other central or local government employee |

10 |

0.9 |

| Law student (university, postgraduate) |

9 |

0.8 |

| Law student (other) |

7 |

0.6 |

| Law student (GDL) |

6 |

0.5 |

| Member of the judiciary (from a legal professional background) |

4 |

0.4 |

| Client/consumer of legal services |

4 |

0.4 |

| Costs lawyer (including trainees) |

3 |

0.3 |

| Law school support staff (including careers consultants) |

3 |

0.3 |

| Ministry of Justice employee |

3 |

0.3 |

| Will writer |

2 |

0.2 |

| Claims manager |

2 |

0.2 |

| Legal regulator employee |

2 |

0.2 |

| Trade mark attorney (including trainees) |

1 |

0.1 |

| Member of the judiciary (not from a legal professional background) |

1 |

0.1 |

| Courts and tribunal service employee |

1 |

0.1 |

| Police or other law enforcement employee |

1 |

0.1 |

| Total |

1128 |

100 |

1.68 Solicitors and trainee solicitors narrowly constituted the largest group (326 respondents, or 28.9%), followed by barristers and pupil barristers (312 respondents, or 27.7%) and CILEx members and trainees (162 respondents, or 14.4%). There was also a strong response from academics and public sector law teachers (64 respondents, or 5.7%), and notaries public (43 respondents, or 3.8%). Thirty-four paralegals (3.0%, two-thirds of whom work in regulated entities) also responded to the survey. With the exception of notaries, the other smaller legal professions are less well represented. For that reason most data has been analysed using the combined categories given in Chapter 1, and generalisation to the smaller occupational groups has been avoided.

1.69 As the respondents to the survey were self selecting the raw data from the survey could not represent the proportionate size of the different professional groups. Consequently the data was weighted to more closely represent the real population. This would make a substantive difference in examination of the mean of all responses. Weighting across all groups would not be possible because of the small number of responses from some groups in the population, and the unknown population size of others. The only viable way to weight responses was thus to strip out those from the smaller occupational groups, and focus on the three major professions, for whom there were an adequate number of responses to make reliable inferences, and for which approximate population sizes exist to enable a proportionate weighting. Where issues of importance arise relating to the smaller professions the unweighted sample is therefore quoted.

1.70 To construct a weighting it is necessary to know the size of the base population. Based on the figures provided or published by the three larger professions, a population of 155,000 in England and Wales was taken as the base figure. This comprises approximately 118,000 solicitors (76.13%),[18] 22,000 CILEx members (14.20%)[19] and 15,000 barristers (9.67%).[20] The weighting factor was produced by dividing the percentage of a profession in the population, by the percentage of respondents from the profession in the survey sample. In the sample 40.75% of respondents were solicitors, 39.00% were barristers, and 20.25% were CILEx members, therefore:

Solicitors = 76.13/40.75 = 1.868

CILEx members = 14.20/20.25 = 0.701

Barristers = 9.67/39.00 = 0.248

These data were programmed into SPSS which produced an appropriately weighted sample.[21]

Table D.3: Comparison of ‘responses’ in the unweighted and weighted Surveys[22]

|

Unweighted Survey |

Weighted Survey* |

|

| Barristers (including Pupils) |

312 |

312 |

| Solicitors (including Trainees) |

326 |

652 |

| CILEx members (including Trainees) |

162 |

486 |

| Notaries Public (including Trainees) |

43 |

0 |

| Paralegals |

34 |

0 |

| Legal Academics/Training Providers |

84 |

0 |

| Law Students |

67 |

0 |

| Other Interested People |

100 |

0 |

| Total |

1128 |

1450 |

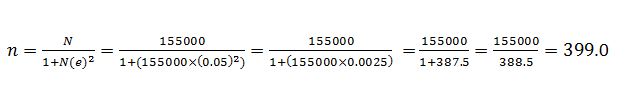

1.71 Another concern may be that with the exclusion of respondents from other occupational backgrounds, there will be insufficient responses left for a reliable sample, and so Yamane’s test was repeated. As previously outlined, there are about 155,000 members of the three major professions in England and Wales (so N=155,000), and the standard level of confidence in social science research is 95% (so e=0.05):

1.72 The research team had exactly 800 responses from people identifying themselves as barristers, CILEx members or solicitors. So after excluding all the other respondents to create a weighted sample of the three main professions, there are at least twice as many as would be needed to be satisfied about the reliability of the findings, (and in the weighting process the sample size is artificially adjusted for an effective size of 1450).

1.73 The sample was in fact generally reflective of the proportions of different identifiable groups in the population as a whole. For instance, there was an even spread of respondents by age:

Table D.4 Respondents to LETR online survey, by age

|

Age Group |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| 24 or younger |

57 |

5.1% |

| 25 to 29 |

138 |

12.2% |

| 30 to 34 |

162 |

14.4% |

| 35 to 40 |

128 |

11.3% |

| 40 to 44 |

144 |

12.8% |

| 45 to 49 |

145 |

12.9% |

| 50 to 54 |

124 |

11.0% |

| 55 to 59 |

115 |

10.2% |

| 60 to 64 |

68 |

6.0% |

| 65 to 69 |

25 |

2.2% |

| 70 to 74 |

14 |

1.2% |

| 75 to 79 |

3 |

0.3% |

| 80 or older |

5 |

0.4% |

1.74 In terms of gender, 52.7% of respondents were male and 46.7% were female, which is a fairly equal split in the sample as a whole, although within certain occupational groups the results were less evenly balanced, for instance 69.6% of barristers were male, as were 74.4% of notaries, while 75.3% of CILEx members were female. These are, however, representative of the gender distribution in those occupations. Other characteristics are in line with expectations: 6.6% of respondents have some form of disability, 5.4% were lesbian, gay or bisexual, and 8.8% were black or minority ethnic. Respondents were predominantly located in London and the South-East (45.5%), but that reflects the geographical imbalance in the profession. Fewer than 5% of respondents lived in Wales.

Table D.5 Respondents to LETR online survey, by location

|

Location |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| London |

298 |

26.4% |

| South East England |

216 |

19.1% |

| South West England |

130 |

11.5% |

| North West England |

103 |

9.1% |

| North East England |

71 |

6.3% |

| East Midlands |

69 |

6.1% |

| Rest of the World |

68 |

6.0% |

| West Midlands |

65 |

5.8% |

| East Anglia |

58 |

5.1% |

| South Wales |

39 |

3.5% |

| North Wales |

8 |

0.7% |

| Scotland |

2 |

0.2% |

| Northern Ireland |

1 |

0.1% |

1.75 Parts of the survey take the form of attitudinal statements, with which the respondents were invited to agree or disagree using a sliding (Likert) scale. The survey sought thereby to explore a number of quite complex and sometimes controversial issues. The language of a number of regulatory terms of art was retained in some of these statements, as there were perceived risks in attempting accurate ‘translations’ of these concepts. As a result, a number of respondents expressed concerns that some questions were insufficiently transparent, biased, or presented false alternatives. Contrary to some of those concerns, there is no attempt to fit the results to any predetermined agenda, but it was necessary to ask questions that examined what the regulators were asking, as directly as possible. While there were some ‘forced answer’ questions, there was always the possibility of disagreement, and the analysis reflects the range of responses received, and has taken account of user concerns.

1.76 The survey data maps against the research questions as follows:

Table D.6: Research questions mapped against key participants and methods

| Research question | Key participants | Methods | |

| i) | What legal skills, knowledge and experience are required of different kinds of lawyers and other emerging roles currently?(content) |

Legal service providers Employers Teachers Students/trainees Stakeholder groups Careers advisers (CAs) Consumers |

Desk research Interviews Focus groups Online survey Careers advisers survey BRDC survey 'Solicitors and their skills' Public consultation (DP 01/2012; 02/2012) |

| ii) | What legal skills, knowledge and experience will be required of lawyers and other key roles in the provision of legal services in 2020?(content) |

Legal service providers Employers Teachers Students/trainees Stakeholder groups Careers advisers Consumers |

Desk research Interviews Focus groups Online survey Careers advisers survey BRDC survey 'Solicitors and their skills' Public consultation (DP 01/2012; 02/2012) |

| iii) | What kind of LSET system(s) will support the delivery of high quality, competitive legal services and high ethical standards(systems and structures) |

Legal service providers Employers Teachers Students/trainees Stakeholder groups |

Desk research Interviews Focus groups Online survey Public consultation (DP 01/2012; 02/2012) |

| iv) | What kind of LSET systems will deliver flexible education and training options, responsive to the need for different career pathways, promoting mobility in the sector and encouraging social mobility and diversity(context/systems and structures) |

Legal service providers Employers Teachers Students/trainees Stakeholder groups |

Desk research Interviews Focus groups Online survey Public consultation (DP 02/2011; 02/2012) EDSM Advisory Group report |

| v) | What characteristics/processes will enable qualification routes to be responsive to emerging needs (eg, of students, training organisations, consumers)?(context/systems and structures) |

Legal service providers Employers Teachers Students/trainees Consumers Stakeholder groups |

Desk research Interviews Focus groups Online survey Public consultation (DP 02/2012) |

| vi) | To what extent, if any, is there scope (and might it be desirable) to move to sector-wide LSET outcomes(content/systems and structures) |

Legal service providers Employers Teachers Stakeholder groups |

Desk research Interviews Online survey Public consultation (DP01/2012; DP 02/2012) |

| vii) |

To what extent, if any, should LSET regulation be extended to currently unregulated groups?(context/systems and structures)

|

Legal service providers Employers Consumers Stakeholder groups

|

Interviews Online survey Will writer survey Public consultation (DP01/2012; DP02/2012) |

1.77 Cross-tabulations allow researchers to ‘slice’ the data into different groups and compare responses. The most important differences examined in this study were those between professional groups, however, there are other comparisons that may have relevance to issues of legal education and training. For instance looking at the different responses of participants divided according to characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, age, disability, and the like could reveal information pertinent to matters of equality, diversity or social mobility.

1.78 Data from the online survey has been used for triangulation, to assess the strength of particular views, to verify issues raised in the qualitative data, and to cast light on specific research questions. In the context of the current report, there has not yet been sufficient opportunity fully to explore the full depth and richness of the quantitative data, and this will be a research pool available for future work.

References

Ezzy, D. (2002). Qualitative Analysis: Practice and Innovation. London: Routledge

Onwuegbuzie, A.J. & Leech, N.L. (2007). Validity and qualitative research: an oxymoron? Quality and Quantity, 41( 1), 239.

Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An Introductory Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row.

[1] http://letr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Susskind-LETR-final-Oct-2012.pdf

[2] As seven of the focus groups were mixed, comprising members from more than one occupational category, this table records both the number of focus groups, and the number of respondents in focus groups, from each sector.

[3] This term was used to include those teaching on LPC and BPTC. Many academics were thus former practitioners. Two at least were in active practice.

[4]Includes those organised for academics in which careers advisers, librarians and in one case students, also took part.

[5] People who introduced themselves as having a training or HR role are included in this total – some were qualified solicitors.

[6] Employment advisers are treated as paralegals for this purpose, whether or not they were in fact legally qualified.

[7]It is worth noting that comments on LLB, LPC, BPTC etc come from graduates as well as current students.

[8] Information on the GDL comes from employers and graduates rather than current students.

[9] For example, topical issues during the research period included the removal of the minimum salary for trainee solicitors, CPD for barristers and for solicitors and the consultation on a separate jurisdiction for Wales.

[11] Briefing Paper 3/2012.

[12] Specifically two large City firms, one mid-sized City firm, one mid-sized general practice firm, one mid-sized legal aid firm and one small legal aid firm.

[13] Briefing Paper 1/2012.

[14]FE, post-1992, Russell Group, 1994 Group, Oxbridge and private providers.

[15] The extent to which the private sector is represented amongst respondents is, given their distinctly vocational perspective, understandable. Numbers are too small for any representative conclusions to be drawn and data from the careers advisers survey has been used in this report principally for its qualitative components including, in particular, understandings of ‘commercial awareness’.

[16] See Briefing Paper 2/2012.

[17] From Office for National Statistics figures drawn from the 2011 Census.

[18] < http://www.lawsociety.org.uk/representation/research-trends/annual-statistical-report/documents/annual-statistical-report-2010—executive-summary-(pdf-392kb)/

[21] Although because weighting is in the cause of statistical representativeness, rather than microcosmic representativeness, it may still appear at first glance as though the weighted proportions favour barristers or CILEx members over solicitors; this is not the case.

[22] Responses in the ‘Weighted Survey’ result from the application of a weighting function to the responses of barristers, solicitors and CILEx members to the LETR online survey.