- Home

- Magazine

- July 2011 Issue

- Law Job Stagnation May Have Started Before the Recession—And It May Be a Sign of Lasting Change

Features

Law Job Stagnation May Have Started Before the Recession—And It May Be a Sign of Lasting Change

Posted Jul 1, 2011 4:40 AM CDT

By William D. Henderson, Rachel M. Zahorsky

The legal profession is undergoing a massive structural shift—one that will leave it dramatically transformed in the coming years.

There’s no doubt that the financial crisis beginning late in 2007 was for most lawyers a game-changer, prompting drastic measures as firms laid off thousands of associates, de-equitized partners, and slashed budgets and new hires.

But many hoped—and still do—that the effects of the recession would ebb, and that the profession, which had just witnessed a golden age of prosperity unmatched by any other industry, would re-emerge relatively unscathed.

The golden era is gone, but this is not because the law itself is becoming less relevant. Rather, the sea change reflects an urgent need for better and cheaper legal services that can keep pace with the demands of a rapidly globalizing world. The Great Recession—a catalyst for change—provided an opportunity to re-examine some long-standing assumptions about lawyers and the clients they serve.

Whether BigLaw lawyers, boutique specialists or solo practitioners, U.S. lawyers can expect slower rates of market growth that will only intensify competitive pressures and produce a shakeout of weaker competitors and slimmer profit margins industrywide. Law students will find ever-more-limited opportunity for the big-salary score, but more jobs in legal services outside the big firms. Associates’ paths upward will fade as firms strain to keep profits per partner up by keeping traditional leverage down.

And those who wish to rise above the disruption will have to deal with technology that swallows billable work, a world market that takes the competition international, and a more sophisticated corporate client with vast knowledge available at the click of a mouse.

NO HISTORY

The biggest problem affecting U.S. lawyers is a failure to understand the origins of our own success. For nearly a century, industry after industry underwent dramatic transformation while lawyers continued to ply their artisan trade. Many lawyers prospered under this conservative path because the substance of what they did was too important to an increasingly complex, interconnected economy.

No more. As the balance of power shifts from traditional law firms and toward clients and a raft of tech-savvy legal services vendors, the price of continued prosperity for lawyers is going to be innovation and doing more with less.

Law touches on virtually every aspect of our social, political and economic lives. As the world becomes more interconnected and complex, new legislation, regulation and treaties bind us all together in ways that promote safety, cooperation and prosperity. Not surprisingly, over the last 25 years government data shows legal services constitute a slightly larger proportion of the nation’s GDP—now nearly 2 percent—with no hint of decline.

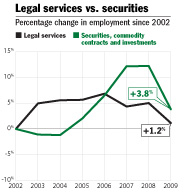

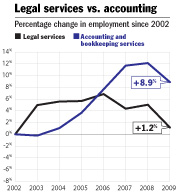

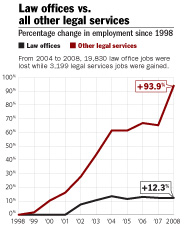

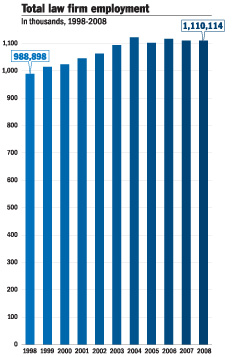

However a very different piece of evidence is the change in total law firm employment, or lack thereof. According to payroll data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau, the multidecade surge in law firm employment hit a plateau in 2004. Between 1998 and 2004, total law firm employment grew by more than 16 percent, or 169,000. Yet between March 2004 and March 2008, several months before the Wall Street meltdown that initiated an unprecedented wave of law firm layoffs, the nation’s law firm sector had already shed nearly 20,000 jobs.

This is a drop in the bucket for an industry that employed more than 1.1 million workers in 2004. But the flattened number of law firm jobs occurred at the same time major law firms in large urban areas were in a bidding war, taking entry-level salaries from $125,000 to $145,000 to $160,000. The public dialogue in the legal press and blogosphere was so fixated on the rising profits per partner at the nation’s top 100 law firms that the broader, systemic patterns went largely unnoticed—at least until the financial fallout descended in the fall of 2008.

By overgeneralizing how well the big firms were doing, we failed to notice a slow but fundamental economic shift affecting the majority of lawyers, who are solo practitioners or in small-to-medium-size law firms.

According to Fred Ury, a former president of the Connecticut Bar Association and a trial lawyer based in Fairfield, Conn., those mainstream lawyers had been feeling the pain for a while.

“The biggest problem,” says Ury, “is that ordinary citizens cannot afford to hire a lawyer. The bread and butter of small firm practices are criminal defense work, wills and trusts, leases, closings and divorces. Yet in Connecticut, 80 to 85 percent of divorces have a self-represented party because most families can’t afford to hire one lawyer, let alone two. Nearly 90 percent of criminal cases are self-represented or by a public defender because families can’t scrape together a retainer.”

Ury, who has practiced in a small firm for nearly 35 years, predicts the problem of unmet legal needs, if not solved by lawyers, “will be solved by technology.”

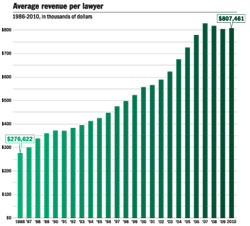

Source: The American Lawyer.

LEGAL, NOT LAW FIRM

The relative high price of legal services creates opportunities for new entrants. Although law firm employment declined from 2004 to 2008, 3,200 jobs were added in all the other legal services categories, which include U.S. jobs with legal process outsourcers and agencies for contract attorneys. But in 2008 the average law firm employee made an average of $79,500 versus $46,800 for a worker in the other legal services groups—and this doesn’t count the wages of foreign outsource workers.

Novus Law is one of the new breed of legal services vendors that combines sophisticated technologies and work processes with an international workforce that operates 22 hours a day. The company specializes in electronic document review for large-scale litigation and corporate due diligence for large businesses. To ensure delivery of a virtually error-free work product on time and within budget, Novus Law engineered an intricate, metric-driven work process certified by Underwriters Laboratories.

Ray Bayley, president and chief executive officer of Novus Law, also perceives a structural shift.

“I think the legal profession has been defined as 250 law firms and lawyers that are licensed to practice law,” Bayley says, “but I view the entire profession as an industry. Over the last 20 to 30 years, virtually all industries have undergone enormous structural change because of globalization and technology.

“The changes affecting the legal services industry began in the late 1980s. They have been significantly accelerated by the recession, and it’s picking up pace. In five years, the profession will be very different.”

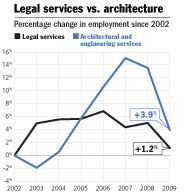

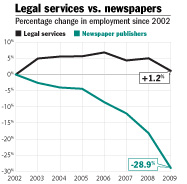

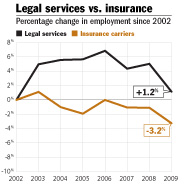

To date, the depth of economic dislocation for U.S. lawyers has been relatively mild, at least when compared to workers in other industries. Manufacturing is the most obvious example, but professions such as advertising, journalism and travel also have been wracked by massive structural changes affecting employment, wages and professional autonomy.

In contrast, total employment in the legal services industry has closely tracked the steady growth rate of government for the past 25 years, with only slight diminution during economic recessions. Yet, from 2006—two years before the financial meltdown—to 2010, employment in legal services began to diverge much more sharply from government.

New economic realities are affecting even the nation’s largest firms. Press releases may still report higher profits, but since 2007, revenue-per-lawyer figures have been trending sideways or down for the majority of the Am Law 100. Like the overall employment numbers for law firms, the stagnation represents a sharp break from historical patterns.

Lower revenue averages indicate slower rates of market growth, intensifying competition, shakeout and slimmer profit margins.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

HOW WE GOT HERE

Over the last century, the traditional associate-partner law firm model has been one of the most enduring features of the U.S. legal profession. However, this remarkable run was made possible by a set of extraordinary economic conditions that no longer prevail.

In the early 1900s as the great industrialists and financiers built their empires, there was a shortage of sophisticated business lawyers. As law firms recruited apprentices on a larger scale to keep pace with business needs, a new question arose: Once the student became the master’s equal, how should the profits be divided?

The most famous solution came at that time from Paul Cravath, who founded the elite New York City law firm of Cravath, Swaine & Moore. Cravath recruited top graduates from leading law schools and developed their skills and acumen through a rotation system that lasted several years. The stated purpose of the Cravath system was to create “a better lawyer faster.”

Dubbed “a law factory,” Cravath’s firm was able to handle prodigious volumes of work and simultaneously train sophisticated business lawyers. As associates ascended into the higher echelon of the firm, the most lucrative reward was partnership. Those who failed to make partner there found the firm’s excellent training opened doors at other New York City firms. Unlike its competitors, the Cravath firm was stable and had the ability to scale its growth to meet the escalating needs of its clients.

Virtually all business law firms in major cities organized themselves along similar principles in the years that followed—growing and prospering from the post-World War II economic boom. Many of these firms emerged as today’s elite brands on either a regional or national level.

But the U.S. legal profession no longer has a shortage of sophisticated business lawyers. Increasingly, clients have become comfortable pitting one firm against another to obtain pricing discounts, and many large corporate clients no longer want to pay the billing rates of junior associates who are learning on the job, excluding first- and second-year associates from working on their matters.

In response, law firms have reduced the number of entry-level lawyers, turning the traditional pyramid structure into a diamond with many senior associates and nonequity partners composing the broad middle. While that makes sense in theory, if the entire industry attempts to shed the training costs of entry-level lawyers, it will eventually produce a shortage of midlevel attorneys and higher labor costs to stave off unwanted attrition. It will also produce a general graying of the corporate bar—a trend evident in much of the Northeast—that will stifle firms’ ability to innovate.

In many respects, the short-term needs of established law firms to generate higher revenue and profits to retain the firms’ biggest rainmakers are at odds with long-term needs to invest in a more sustainable business model tied to the changing demands of clients. The sheer size and geographic dispersion of many firms, along with the limited time horizons of their current partners, make change unlikely. Yet as firms resist change, their clients become more likely to vote with their feet: taking more work in-house, experimenting with smaller-market/lower-cost firms or giving work to legal process outsourcers, all of whom have greater flexibility to innovate.

The 21st century is sure to give rise to a new generation of legal entrepreneurs who create novel ways to adapt to the needs of clients. Successful innovators will grapple with the three interconnected forces that make change inevitable:

1) More sophisticated clients armed with more information and greater market power to rein in costs.

2) A globalized economy, which increases the complexity of legal work while exposing U.S. lawyers to greater competition.

3) Powerful information technology that can automate or replace many of the traditional, billable functions performed by lawyers.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

IN-HOUSE RULES

Perhaps the group most acutely aware of the drumbeat of change—and striking the tom-tom themselves—are corporate general counsel. Regardless of the size of a company’s legal budget, clients want to control their operating costs. And that includes legal services.

Lawyers still possess specialized knowledge only intelligible by studying case law and attending law school. But the overabundance of free, online information has created lawyer-client relationships that are more symmetrical in terms of information. Social networking tools also place the wisdom of crowds at the fingertips of individual consumers. If lawyers are good, clients will find them, but the clients will also find their closest competitors. The tactics needed to win business are thus likely to be more sophisticated and targeted.

In the corporate realm, general counsel are increasingly expected to achieve what other departments and businesses do—get better results at lower costs. No longer viewed as purveyors of the law, in-house lawyers are problem solvers and key business strategists. The multimillion-dollar budgets that flowed unchecked into the coffers of the nation’s largest law firms are now closely guarded and counted.

“There is no question that a serious recession caused a heightened sense of awareness for law firms and consumers,” says Gregory Jordan, who works out of Pittsburgh and New York City as Reed Smith’s global managing partner and chairman of the senior management team and executive committee. “As the recession starts to reverse itself, there will be some movement away from that super-heightened awareness of cost, but this recession gave buyers of legal services enough time to really appreciate that they could get the same quality of service for less than before the recession. The better, faster, cheaper concept is very much here to stay.”

Although most general counsel begin their careers at traditional law firms, they are increasingly influenced by the business practices of their fellow corporate managers. In some cases, this means new procurement practices for legal services, using technology to speed up or automate routine legal tasks, or building in-house expertise that is core to the company’s strategic objectives. When general counsel do turn to outside counsel, they have the ability to pit one law firm against another to achieve competitive rates. And although clients may continue to stay in a long-established relationship with a firm, that doesn’t guarantee they’ll return with new matters or refer colleagues.

General counsel should be careful, however, not to overplay their hands. Although chief legal officers want their outside counsel to have shared risk or “skin in the game,” general counsel who meet their annual budget by pushing for discounted fees are unlikely to get the best long-term results. The key to doing more with less is innovation, often achieved by long-term relationships and shared information. This requires mutual trust and a willingness to share risk over time.

Some Fortune 500 companies have adopted the presumption that all legal work will be done in-house. General Electric’s legal department and others have lawyers in India supervised by in-house lawyers in the U.S. And Cisco Systems built a Web-based knowledge management system that captures email conversations, facilitates secure communication with experts, and documents answers to frequently asked questions—all to boost in-house productivity and cut the law department’s expenses.

On Main Street, while the average baby boomer client doesn’t want to create a will or trust online, 20-year-olds, soon to become the typical legal consumers with families, are so used to conducting their business on the Internet that that’s how they’ll also buy their legal services, says Ury, founder of Ury & Moskow. As Generation Y and Millennials ascend the corporate ladder and amass wealth, will they be just as apt to purchase more sophisticated services online? “Probably not,” Ury says, “but they will come with their own drafts.”

“My clients do that now,” says Ury, adding that clients are more apt to bring a contract or lease for his review rather than request a draft done by his law office.

In the future, Ury predicts, nearly all legal forms and commoditized services will be free of charge. He points to the Connecticut secretary of state’s website, where hundreds of forms are available to download, including divorce petitions and business filings.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

E-LAW

Technology is replacing many of the tasks formerly performed by lawyers. From a social point of view, this is very desirable because it drives down the cost of legal services and satisfies unmet legal needs. From an industry view, however, it can be a gut shot to the bottom line.

Incomes of ordinary middle-class citizens have stagnated while the relative price of legal services has risen. Unmet legal needs are on the rise, opening the door for inexpensive, Web-based legal services providers that essentially offer do-it-yourself kits for many personal or business legal needs.

One such provider, LegalZoom, has had more than 1 million customers in its 10 years online. The Practical Law Co. has created a similar line of form documents and annotations that deal with many of the most sophisticated transnational and compliance issues facing large corporate legal departments. And Cybersettle claims it has resolved more than $1.6 billion worth of cases in the last 10 years.

Using technology to tap into the mass consumer or business market, however, requires more than a great idea. Also necessary are access to capital and the ability to collaborate with professionals in other disciplines, such as system engineering, knowledge management, marketing, finance and project management. Few lawyers have the time, financial wherewithal or risk tolerance to play in this league.

For most lawyers, survival will depend upon their ability to harness technology to deliver greater value to clients at a cost that declines—yes, declines—over time. The biggest challenge for law firms will be transitioning away from internal firm metrics that reward billable hours and discourage or prohibit the crucial trial-and-error experimentation needed to create, refine and market more innovative work processes that do more with less.

At a minimum, law firms need to return to the concept of sharing risk among the equity shareholders and retaining earnings to finance new technologies, training, and research and development.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

GLOBALIZATION

Moving forward, globalization represents both the greatest challenge and greatest opportunity for lawyers.

As the world becomes more interconnected, business relationships rarely will stop at national borders. Basic family law issues will inevitably bump up against immigration law. Sales of goods and services over the Internet raise complex issues of international tax. Exploiting and protecting the value of any domestic innovation requires a strong grasp of international intellectual property law. A client who opens an office or facility in a foreign country faces a dizzying array of legal issues that must be quickly and efficiently analyzed before a business decision can be made.

The flip side of this business opportunity, however, is that few clients have the ability or willingness to pay for this service under the traditional law firm model. It is either too slow, too expensive or too unpredictable. Globalization exposes clients to an international workforce that is often hungrier and completely unwedded to past practices.

As the global economy matures, the push for increased regulation will also boost demand for sophisticated business lawyers. This has a twofold effect: Prominent U.S. firms, specifically among the 250 largest firms, are expanding global operations—a costly venture that will be unobtainable for some. And U.S. lawyers, particularly young associates and freshly minted law school graduates, face fierce competition for work from overseas counterparts.

“The goal of clients in big cases is to play it safe,” says William Reynolds, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Law. “And playing it safe is to hire the best lawyers—and those aren’t in India.”

But what if, in the coming years, they are?

U.S. lawyers underestimate the threats of foreign competition to the provision of domestic legal services. The realm of “all other legal services providers,” which grew from less than $1 billion in total revenues in 1997 to nearly $3 billion in 2008, will continue to attract sophisticated business capitalists eager to obtain a greater portion of U.S. corporations’ legal budgets.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Lower-level “commodity” legal work is already being sent to developing markets like China, India and the Philippines because wages are lower and the multiplying workforce is eager. Staff positions doing document review and slogging through discovery are highly coveted by a booming, educated middle class in a culture where law firm jobs often go to those at the top of the caste system. And quality, consistency, security and efficiency concerns have been quelled by legal services providers such as Pangea3 (acquired by Thomson Reuters), which is building facilities across the U.S. modeled after its India operations, and Chicago-based Mindcrest, which has facilities in India.

In fact, quality control is an easy concern to eliminate when working on large-scale projects for corporations because of the rigorous methodology and processes employed, which law firms often overlook, according to Ganesh Natarajan, Mindcrest’s co-founder, president and CEO.

As a result, these facilities become the perfect laboratories for developing more sophisticated legal work processes. Akin to the Japanese car manufacturers who started with cheap economy cars in the 1970s and eventually created the brands that challenged Cadillac and Lincoln, foreign legal workers are destined to become a formidable economic force.

For those firms at the apex of the profession, the pressures of change may not be felt as heavily as by their midlevel counterparts, causing some law firm leaders to doubt the magnitude of the tremors affecting the industry.

“I’ve seen various waves of purported reform crash on our shores,” says Peter Kalis, chairman and global managing partner of K&L Gates. “I see no paradigm shift in the business of law. What I see are evolutionary adaptations to changing market conditions.”

Even so, Kalis says his firm’s aggressive global expansion in recent years is the result of client demands for cross-border expertise—and firms that can’t meet those demands could fail.

“In a world where even modest-size clients compete in global markets, they are going to need law firms positioned to address that,” says Kalis, who works out of the firm’s New York City and Pittsburgh offices. “There will be a lot of casualties among firms not on the right side of history, and they will be the last to know until talent and clients start to migrate to other firms.”

Whether the changes affecting the legal profession are indeed a reflection of market cycles or a complete paradigm shift will become evident in coming years. But for those betting substantive change has not happened, they are betting their practices against the future.

William D. Henderson is director of the Center on the Global Legal Profession, and professor of law and Nolan Faculty Fellow at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law. He received his JD from the University of Chicago in 2001. Rachel M. Zahorsky, a lawyer, is a legal affairs writer for the ABA Journal. She can be reached at rachel.zahorsky@americanbar.org.

Comments

Fed JD

Jun 27, 2011 2:54 PM CDT

May have? I was unemployed for year after I graduated and passed the bar in 2007. It’s a terrible market and law schools aren’t helping.

Ted Brooks

Jun 27, 2011 5:57 PM CDT

This is certainly interesting. The technology that helps make things efficient also has the potential to replace people. For what it’s worth, here a couple of recent articles from my blog on the topic of legal technology. One deals with replacing Court Reporters with technology, the other deals with using technology in trial (which at least doesn’t replace lawyers).

http://trial-technology.blogspot.com/2011/05/court-reporters-legal-videographers.html

http://trial-technology.blogspot.com/2011/06/top-12-reasons-attorneys-should-be.html

Rishi S. Bagga

Jun 28, 2011 1:14 PM CDT

I too have experienced this first hand. Graduated in 2006, when times were still good, and went through a more traditional hiring path (big prosecutors office, thought i’d go big firm afterwards)... when the reality hit hard. Now doing solo/small firm work, with an LLM, and focusing on small businesses and individuals. Incorporating as much technology to make it easy for clients to communicate with me as well, which has been successful so far.

I agree with the comment above - law schools are part of the issue here. To be very brutal, we have far too many - the surge in the number of law schools, many of whom are attorney-factories (and quality appears to suffer a little, at least in my experience), is not helping. As bad as it sounds, I think the ABA needs to work towards whittling down the number of law schools, especially of the for-profit, unaffiliated variety. Demand has clearly declined, and over-supplying is the wrong approach.

Ollie

Jun 29, 2011 6:14 AM CDT

When I helped my spouse cram for her bar review exams 30 years ago, I remember discussing whether she should sign up for the ABA. She concluded that she shouldn’t because at the time she thought they were holding the profession back.

She’s had a terrific career working in-house and helping create great value for her employers by requiring that their legal work be done efficiently and transparently.

Help create value for your client! This is the way to be respected, whether it’s in licensing, divorce, real-estate, or anything else.

MH

Jun 29, 2011 9:02 AM CDT

Great article. Where’s the part about law schools claiming 98% employment by 9 months though, for every single year up til 2009.

Julie

Jun 29, 2011 9:45 AM CDT

“For nearly a century, industry after industry underwent dramatic transformation while lawyers continued to ply their artisan trade… No more. As the balance of power shifts from traditional law firms and toward clients and a raft of tech-savvy legal services vendors, the price of continued prosperity for lawyers is going to be innovation and doing more with less.”

I couldn’t agree more! The ABA and law schools have been irresponsible and greedy. They’re a significant factor in the state of the legal market. But, if lawyers could move beyond the antiquated visions of law and move their mindset into the 21st (or just past the 1980s), there are endless opportunities for innovation to open up the market so that more people have access to legal services and more lawyers have jobs,

Akiva Cohen

Jun 29, 2011 11:52 AM CDT

This is an excellent piece. Indeed I think the legal industry has dramatically changed in the last decade and is set to continue. On the litigation side, document review and financing are being outsourced. On the corporate side you have outside general counsel companies like Axiom and Outside GC. There are also a growing set of alternative law firms like Clearspire, Rimon, VLP, and many others. I think this downturn will lead to continued disruptions and innovation.

Jared

Jun 29, 2011 12:49 PM CDT

I created a website that tracks time in meetings with your lawyer. It’s seen a good amount of traffic recently. Rates have been sticky for way too long.

http://www.lawyerclock.com

Rob Dean

Jun 29, 2011 3:15 PM CDT

Consider Ury’s comment that “ordinary citizens cannot afford to hire a lawyer…[n]early 90 percent of criminal cases are self-represented or by a public defender because families can’t scrape together a retainer.”

Small law firms are getting crushed by the pace of technological change. Many recent law grads could handle twice the case load of a typical criminal defense attorney in town, mainly because they grew up on the Internet, but most small law firms are stuck operating an inefficient business model.

As another commenter noted, “Our offices were expensive. Our parties were expensive. The I.T. support was expensive because it had painted itself into vendor lock-in and a huge (and useless) support staff.” For small law firms, it’s a straightforward solution: lower fees, lower costs by leverage free technology, and still increase income.

Small law firms need to win back the middle class, and it starts with lower fees, as I discuss here:

http://www.walkingoffice.com/?p=1163

Karimah Boston

Jun 29, 2011 9:20 PM CDT

I was just talking to a 2L today. I told her to try to find the practice area that interested her the most this year and treat her third year like an apprenticeship so she would be better prepared to hang out her shingle rather than vie for a big firm job. I think everyone has to abandon the idea of hundreds of lawyers working for one firm and get used to 100 solo practitioners each with their own specialty.

LSTB

Jun 30, 2011 8:12 AM CDT

Of course law job growth stagnated before the housing bubble burst. In fact, job growth in the U.S. legal sector was stagnant throughout the 1990s and no one noticed. BEA data show that real legal sector output simply stopped growing after 1990, and its growth in the dotcom and housing bubble eras never really kept up with the U.S. economy.

Thus, the lack of law jobs hasn’t been due to reckless law school expansion (that happened in the 1970s), globalization, in/outsourcing, e-law, etc., but the fact that law schools make money regardless of the legal sector’s performance.

Scott

Jun 30, 2011 11:54 AM CDT

@9; agreed.

As the OP states, “strain to keep profits per partner up by keeping traditional leverage down”. As always, the underlying premise is profits (greed). Rather than give up profit and hire new folk, they’d rather take the cash because mama needs a new fur coat or a Beemer.

Case in point:

#1. I visited an attorney in 2005 for a black mold / water issue with my house that I purchased in 2004. He wanted $3,000.00 as a pre-payment before doing any work.

#2. Instead I joined the Prepaid Legal Services which costs me $24.00 per month and received the name of an attorney on their staff in my local area.

By April of 2006 I contacted her and this attorney for Prepaid called me and asked me for my realtor contract, description of the issues, and the seller’s names and address. One month later, I had a check from the seller for $5,000.00. Total cost for my time was about $288.00.

That folks, is value-added to as a customer. Asking me for $3k upfront is non value-added and an insult. I am not obligated to help pay someone’s mortgage or boat loan. What I will do is pay for services that are reasonably priced and value-added.

The lawyer business model is terribly outdated and broken.

JMF

Jun 30, 2011 12:55 PM CDT

Thank you for an informative piece, ABA. Perhaps the ABA can become a vital force (and truth-teller) again after what seems like a period in which it has been mired in bureaucracy and out-of-touch with the current state of the legal profession. If so, I’ll renew my membership.

sba

Jun 30, 2011 7:53 PM CDT

But many hoped—and still do—that the effects of the recession would ebb, and that the profession, which had just witnessed a golden age of prosperity unmatched by any other industry, would re-emerge relatively unscathed.

Stopped reading here - has the author heard of the financial services industry? ( Or maybe of hedge fund managers?) They dwarf any “golden age of prosperity” by the legal profession.

And what is this, an industry or a profession?

Young Lawyer

Jul 1, 2011 6:34 AM CDT

This is a cute story but where is the story where the ABA takes some responsibility for creating the glut of lawyers? You accredit the seedy for-profit institutions across the nation so, to many law students, they appear to have the same credentials as school that have suffered the test of time and proven their merit to the legal community. These schools produce a lower quality lawyer to create an glut in the community. After all, a lawyer is a lawyer, right?

Instead, the only thing that we hear from the ABA goes something like this:

New Lawyer: What a joy to graduate from such a prestigious law school!

ABA: You were a chump for going and have no possibility of paying back the massive debt you have accrued. Have you renewed your membership yet?

As a side note, I’m one of the lucky ones and I have a job post law school. Law schools, no doubt, have a responsibility to the legal community to reduce costs on law students. 100-150K debts should not be standard for a profession that, on average, will only make 1/2 of that in pay per year. However, the ABA needs to step up and increase the criteria on accrediting. Maybe even include a criteria like “value to the community it serves” to remove law schools that are simply (poor quality) attorney factories. I know that my state and many others won’t even allow you to sit for the bar if you attended a school that was not accredited by the ABA. In essence, get back to serving the legal community from bad law schools. Until you get started on that, don’t bother asking me for anything else.

Paul

Jul 1, 2011 7:26 AM CDT

When is the ABA going to actually offer meaningful regulation and oversight of its schools? the employment statistics being published by schools (think thomas jefferson school of law) are neither fair nor accurate, but they are within ABA guidelines. who watches the watchers? the ABA is encouraging a system which gives false promises to prospective students who rely on fair and accurate information on employment prospects before committing to six digits of debt, but are given data that misrepresents the reality of their prospects. the ABA should be ashamed of their role in oversaturating the legal market and destroying the lives of thousands of students who assumed they would be among the “98% employed” upon graduation, but find themselves jobless and saddled with a mortgage before they even bought a house.

B. McLeod

Jul 1, 2011 7:28 AM CDT

What? Huge mega-firms with creative billing practices, killer overhead and a blindness to positional conflict are not the best and most efficient platform for legal service delivery?

Now that’s just crazy talk.

R. Swain

Jul 1, 2011 8:28 AM CDT

Good article and the writing on the wall has been there for a long time. The ABA certtainly is a big part of the perception problem and that is why I only have been a member when someone else pays my dues. No real value there. Insurance companies have been looking for value added and cost control agreements for years. Private counsel that commands big bucks on an hourly basis have to prove that there is a return on that cost. There is a reason for the lack of client loyalty any more. Advertising and ability to compare results and costs mean a real restructuring. This includes in house and if you don’t invest, you will be left behind.

Damon

Jul 1, 2011 9:30 AM CDT

@12

Scott - what you don’t know is how much of a recovery you would have recieved by the $3000 lawyer. If he had gotten you a $12k (or even a $9k) recovery, you would have netted out better. Fees alone should never justify which lawyer you choose.

As a GC for public company, I carefully consider all factors before selecting outside counsel. Fees are an important consideration, but also are overall skill, expertise in the particular area of law, industry knowledge, and reputation. The one thing I readily agree with is that it’s definitely a buyer’s market for legal services. I recently did and RFP for and received responses from several BigLaw firms (including a firm which I previously used, which agreed to discount its fees from what it was normally charging us).

James

Jul 1, 2011 9:54 AM CDT

Prepaid legal has its place. When all you need is a “letter from a lawyer” then spending $288 may be just fine. The “letter from a lawyer” only gets results when it carries with it the implicit or explicit threat of litigation. If you think you are going to avoid paying a lawyer’s mortgage when it gets to the point that the $288 letter is just plain ignored and you have to actually DO SOMETHING in court, you are mistaken.

We all know of cases where the $288 for the letter was money wasted and the client STILL had to go out and pay the $3,000 retainer later, bringing the initial bill to the HIGHER figure of $3,288 [plus $24 per month you pay to the non-lawyer]. In other words, pre-paid legal can actually COST you more money than it saves in some cases.

ECS

Jul 1, 2011 10:24 AM CDT

This article ignores one HUGE reality. (And one smaller/related one.) Lawyers are grossly lacking in communication and relationship building skills—in business and in their lives. This luxury is no longer available to those who want to provide what clients want/need. (Technology and outsourcing don’t provide this either,

The smaller issue is public perception, as illustrated by Scott’s black mold story. Yes, Prepaid, We the People and Legalzoom seem better and cheaper. to Joe Ordinaryguy.. and they are—unless they aren’t. Alas, the public does not know when they are and when they aren’t. BUT LAWYERS ARE NOT TRUSTED.

So we have screwed ourselves, with a lot of help from the Larry Parkers and Robert Shapiros (and Judge Ito’s) of the world.

Bill

Jul 1, 2011 10:36 AM CDT

This article is dumb. So are the people that continue to talk about the 98 % employment after graduation. We all know already. Go do something with your lives. If you suck as an attorney, good luck. If you are good, none of this will apply.

faddking

Jul 1, 2011 10:51 AM CDT

“Yet between March 2004 and March 2008, several months before the Wall Street meltdown that initiated an unprecedented wave of law firm layoffs, the nation’s law firm sector had already shed nearly 20,000 jobs.”

That’s because the recession of 2001-2002 never really ended. The Housing Bubble was responsible for “prosperity” in this country from the Recession of 2001 until the start of the Great Recession. If you were working during that period of time, and had already been working for a number of years before that, you KNEW on a gut level that things weren’t quite on the up and up with the economy. I graduated high school in the 1980s and have seen a number of economic ups and downs. Between 2001 and 2008, there was something that just didn’t feel right with the economy. People were living on credit, not economic success.

Right

Jul 1, 2011 10:54 AM CDT

The legal profession is fundamentally parasitic. Legal work does not create value. In the best case scenario a lawyer can reduce the destructive force of regulation. Even making a client “whole” is a net loss. It is no surprise that after 40 years of falling wages America isn’t as capable of feeding a profession that by and large only exists to grease the wheels of the system lawyers created for their own benefit.

Esq.

Jul 1, 2011 10:58 AM CDT

It’s a bubble, pure and simple. I started law school back in 2000 when the big firms were paying $125k. Within six years the salaries had increased 30% to $165k, even though the majority of those years were recession times.

Patrick

Jul 1, 2011 11:48 AM CDT

@ 12: The $3,000 was almost certainly a retainer—if $288 worth of lawyer time had gotten you an adequate settlement, your lawyer would have reimbursed the remaining $2712.

I’m also a little concerned that you signed up for pre-paid legal AFTER you knew you were in need of legal services. The prepaid legal services I have had experience with operate like legal insurance; you pay a premium, and if a need for legal services arises, your prepaid service will cover the cost. Signing up for prepaid legal after you knew you needed a lawyer, and because you did not want to pay a lawyer out of pocket, might have been like getting car insurance after totalling your car. I hope that’s not what happened in your case.

Finally, and this is important, there are good lawyers and bad lawyers. Any lawyer can get you a settlement with virtually no work, but there are not too many lawyers out there who will really fight to make sure that settlement reflects the value of your claim. On that note, I am curious to know whether you were able to have comprehensive mold remediation work done on your home for $5,000.

Myth

Jul 1, 2011 11:59 AM CDT

“Lawyers still possess specialized knowledge only intelligible by studying case law and attending law school.”

This is the myth that’s still working for us. When it falls away, the profession will be in real trouble. But it is a myth. I learned more that’s useful to the practice of law in 2 months of BARBRI than in 3 years of law school at Texas.

Waste Land

Jul 1, 2011 12:48 PM CDT

Consider this:

1. “The biggest problem,” says Ury, “is that ordinary citizens cannot afford to hire a lawyer.”

2. There are a heck of a lot of attorneys out there looking for a job.

3. The obvious answer: hanging a shingle and offering prices that a) the attorney can survive on and b) that a majority of people can afford.

Of the attorneys looking for a job, many have toyed with the idea of hanging a shingle. The problem? The waste land that exists between the lowest amount an attorney can afford to charge after including overhead (cost of insurance, monthly law school loan payments, rent, food, bar memberships, advertising, office supplies, software, assistants, suspended payments in trust accounts, etc) and the price that 90% of the population can afford to pay for an attorney.

It just doesn’t add up. And I am constantly surprised that no one directly addresses this very big elephant.

I understand that there is a need for some regulation because, unfortunately, there are always some bad apples in the barrel. And I understand the need to mandate liability insurance - the cost of which has gone up significantly due to the fact that more and more clients are suing their attorneys (based on more and more regulations that attorneys are forced to keep up with).

But ask yourselves - what would it take to ensure that young lawyers are able to go straight from law school to their own practice (an option that is legally and rightfully available to them - although you wouldn’t know it from some of the wise old soap boxers on these comment boards)?

“A self-taught lawyer with only one year of frontier schooling, Abraham Lincoln rode his horse into Springfield in 1837 with all his belongings in two saddlebags.” (Lincoln Home brochure). He became a very successful attorney and…well…I think we know the rest.

I think there are a lot of young attorneys who would give their right arm for the opportunity to ride into town on a scooter with all of their belongings bungee corded to the back. An opportunity - a chance to help some people and show everyone that they are indeed as good an attorney as the state bar proclaims. But who can afford to? And then with all of the industry regulations and constant threat of harsh punishments hanging over their heads, who is crazy enough to want to?

I’m afraid the entrepreneurial branch of the legal profession is headed the way of the dinosaurs - at the expense of 90% of the population, and a young attorney’s dream.

Young Lawyer

Jul 1, 2011 4:16 PM CDT

@24 You couldn’t be further from the truth. No doubt that law and the legal profession exists because society exists. After all, laws are just an arbitrary boundary to make people just comfortable enough with their next door neighbor as to not kill them (most of the time). That is not to say that the relationship is not mutually beneficial nor does it logically conclude that lawyers do not create value.

Lawyers create value all the time. For example, contracts that allow for international trade where none would exist in the absence of such a contract. As well, consider intellectual property rights that allow for the protected use and development of an idea that would not have been profitable enough under open market competition to use (mostly because it would be used by others as soon as the inventor is done with the work). Software was once thought of as only marketable as part of a physical computer and now some of the most valuable companies in the nation are related to the production of software that is only incidentally related to hardware. There are many more examples in places such as commercial paper, oil and gas, and corporations.

Surely, mitigation of damage is a large part of what lawyers do, but this is only because there is no limit to the harm a person can do to themselves. People are extremely novel at hurting themselves. We exist both to protect people from the harm they do (to themselves or others) and to assist the beneficial growth of a society through the implementation of law. Without law, and the administration thereof, our society would not be able to develop the products it develops. Providing that opportunity IS lawyer-created value.

lex

Jul 2, 2011 2:35 PM CDT

Lawyers should be requiredf to advertise their prices and compete. The whip lash willie advertising we see is embarrassing to the profession. Let thge whip lash willies compete based on price, not just on claiming (sometimes with exaggeration) they will be bring a person millions.

Laywers in law firms make too much money.

Its simply wrong, wrong, wrong.

ECS

Jul 3, 2011 1:50 PM CDT

Lex—PARTNERS at Biglaw make too much. For now. Their fatcat days are numbered.

B. McLeod

Jul 3, 2011 4:13 PM CDT

Even when their mega firms disintegrate, the partners with real books of business will still do fine, as long as they can find a half-dozen starving “associates” or “staff attorneys” to hitch to the sled (which looks like the indefinitely foreseeable future).

sunforester

Jul 4, 2011 10:50 AM CDT

It’s about time that lawyers recognized that we are both an industry AND a profession. There has always been a need for lawyers, and now the market is defining exactly how much we are needed. It is fair and just that the buyer finally is in a far better position to choose who to pay and how much, especially that the casino money that freely flowed with all the bubbles we have suffered these past few decades (thank you, Bill Clinton) is now officially off the table and no longer skewing the behavior of the market and its perceptions.

Lawyers who refuse to recognize market realities will find that their fates suffer accordingly. Lawyers who blame the ABA for not making all things better for themselves put too much faith and trust in the ABA. Lawyers who deeply believe that principle should trump money every time are babes in the woods. This article gets pretty close to reality, and should be taken seriously.

mary

Jul 5, 2011 9:05 AM CDT

What if there was a national bar exam, with a very low pass rate, wouldn’t that reduce the glut of lawyers?

AndytheLawyer

Jul 5, 2011 12:40 PM CDT

#34—You’ve just described Japan. But unlike Americans, the Japanese have other means of dispute resolution that don’t require lawyers’ involvement.

Right

Jul 5, 2011 3:20 PM CDT

#34—you’ve just described a cartel, apparently a cartel with a tighter reign than the ABA. The above guy who ineptly responded to my description of the profession as “not creating value” would do well to pay attention to the broken window fallacy.

Ariel Bender

Jul 6, 2011 7:40 AM CDT

“But the overabundance of free, online information has created lawyer-client relationships that are more symmetrical in terms of information.”

Man, I hate it when my relationships become symmetrical in terms of information! I’d much rather they be obtuse in terms of data accessing capability or bilateral vis a vis dialoguing.

Very snappy prose.

Nick

Jul 6, 2011 3:44 PM CDT

@29: your points are well taken, but I think we need to re-evaluate the influence of the legal profession on the U.S. economy in particular, and whether we are in fact “overlawyered” to the extent we are hindering, and not aiding growth.

Countries like Japan, Germany and China are far less litigious than the U.S., and have far fewer attorneys per capita, and, coincidentally are growing at faster rates than the U.S. While it’s not necessarily a direct correlation, it stands to reason that if there are fewer attorneys and fewer law suits, businesses can direct more money toward producing goods and delivering services. While some will argue that more regulation is needed to ensure a high quality of life and protection from corporate abuses, I would note that the quality of life in Germany and Japan is on par with, and probably higher than in this country. So, I don’t think anyone in those countries is bemoaning a lack of lawyers.

John

Jul 7, 2011 7:12 AM CDT

Respectfully, I agree with hardly a word written by the author:

1) Most lawyers represent the 99% of Americans whose income and opportunities have been declining for 30/35 years. 2006 was the last good year because it was the last year that these Americans could borrow to sustain their purchasing power. Consequently lawyer income and opportunity has been declining and will continue to do such until the rules of life are re-set and income is taken from the wealthy and redistributed. Distribution of income is always a political question and the social contract in America has been broken for 35 years.

2) Large law firms sold their souls in the Central Bank, Stoneridge, Janus Capital triology of cases. You look at lawyers who works for big law, now, and you see evil, sick, disgusting people, who add no value to our society. They have a duty to zealously teach and counsel their clients how to lie, cheat and steal. The law is that it is lawful for their clients to aid, abet, counsel, and encourage securities fraud. Therefore, they have a duty to counsel their clients how to aid, abet, counsel, encourage, and even document securities fraud. Who would have anything to do with such people? Even if the laws were changed, it would take 3 generations for the profession to recover what it has lost since 1985. It is morally very equivocal for the legal profession to exist representing past wrongdoers. There is no place for a profession that counsels how to commit evil and yet this is what the profession sought and now does.

3) Last, and most importantly, we have become a lawless society. Only a fool hires a lawyer. One just steals and walks away with the profits, if one is smart. Look at the recent story about Bank of America, which is paying $8.5 billions to settle claims that it committed fraud in the packaging of mortgage loans into securities. The shareholders and taxpayers (the Bank is too big to fail) are stuck with the bill. However, not one person—-borrower, loan officer, appraiser, manger, lawyers, or broker, is going to be named or held responsible in any way. Demand for legal services will return only when we become a society where individuals are held responsible. For example, there would be plenty of legal work for everyone if all who stole money by making false loan applications were prosecuted, but no one has been out of the millions of loans made. Similarly, we have 12 million illegals in this Country. They is more legal work than one can shake a stick at. These people should be arrested, tried, and deported. Their presence depresses wages for American citizens (and thus reduces lawyer income)

4) Opportunity. Lawyers must come to understand that globalization destroys opportunities for most clients and thus for most lawyers. Only the largest, most sophisticated clients are doing business in India or China. 95% of American firms and businesses or more will never make a dollar in profit from either country. Lawyers need to realize that their future lies in the re-creation of opportunity, here. For example, if taxpayers fund basic research at an America university, when it comes time to incorporate those ideas into products, the law (and lawyers) ought to insist in those products being made here. How is it moral (and hence law abiding) to tax someone to create jobs and profits for a manufacturer in China?

Just the facts, Ma'am

Jul 8, 2011 1:42 PM CDT

If you practice a real meatball kind of law I suppose you could learn more in BarBri than in law school. There was nothing in BarBri that prepared me for my practice.

1991lawgrad

Jul 10, 2011 12:33 PM CDT

@39 - and let us not forget that legal service employees in China, India, etc. are not paying taxes, social security or spending any amount of meaningful in money in the US. I’m not an economist, but this is starting to look like another loopsided export, cash and jobs go out, while another class of white collar jobs disappears, along with other intangibles, made possible by those white collar jobs, which drive local economies, PTAs, sports teams, college educations for the next generation, etc.

B. McLeod

Jul 10, 2011 5:06 PM CDT

Sure, but it drives them in Japanese-made cars.

WrB.

Jul 11, 2011 12:49 PM CDT

The article speaks to innovation in the midst of opportunity/sea change. The legal field is neither an industry or a profession; though, there are judges and there are barristers, etc. To take from Llwelyn: law is about disputes.

As a system inextricable from government, those who participate in lawyering and judging participate in government. As someone who has not attended law school or been dubbed by the ABA, I may excite little respect, and yet may offer a clear perspective.

The field of law is of course a battleground of regulation, but the battle is a spectacle to be judged also from afar. It seems to me, that there is plenty of dispute in the air: so much so that those big firms would probably be of use.

As to technology and its role in the legal field it can be used to fuel disputes and also settle them. It seems, technology is necessary but not sufficient to put it in LSAT terms.

Lady Justice

Jul 14, 2011 12:20 PM CDT

Saying that you are a lawyer today does not carry the same prestige as it did years ago. Law schools and the ABA are partly to blame. The institutions that were created to strengthen the profession have contributed and continue to contribute to its demise. But, individual lawyers also deserve some blame. For many would-be-lawyers, a legal education became a way to make money, as much money as possible, at any cost. The financial expectations from a law degree kept increasing and society cannot keep up with these expectations, in addition to the over-supply of lawyers. Law schools also jumped on the bandwagon of the money train and became profit centers for the benefit of a few (the highly remunerated administrators and faculty), the most connected and credentialed, but not necessarily the most qualified, ethical or hard working. The ABA saw the increasing number of lawyers as a way to increase its subjects and fee-payers. It’s a sad, vicious circle, all around.

This is the end

Jul 16, 2011 12:03 PM CDT

Far too many law school function as nothing but pyramid scheme. It’s simple. The student loans that are federally guaranteed and are given to virtually everyone function as a wealth transfer vehicle from penniless 20-year-olds to greedy academicians. The only thing those “academicians” at schools like Cooly or TJSL need is a rubber stamp to thrust students into financial ruin, and that’s where the ABA comes in. They have directly allowed this pyramid scheme to work. The ABA was supposed to strengthen this profession but has instead created a vast over-supply of lawyers by knowingly accrediting more institutions that produce far more lawyers than what the industry has demand for. The law schools are furthered supported by being allowed to give obfuscated and deceptive employment statistics to prospective students, luring them to take on six digits of debt on the basis of fundamentally flawed information. What the ABA has allowed should be criminal in and of itself, but then again, many of its members are faculty at these low-tier schools that have a vested financial interest in maintaining a system that profits them at the expense of harming students and the industry.

The ABA is an unethical institution which should not be supported any longer. It has been corrupted to its core.

B. McLeod

Jul 16, 2011 1:53 PM CDT

And yet, it has its dark side, too.

Scott

Jul 17, 2011 9:32 AM CDT

@19: I didn’t want or need $9k or $12k. All I wanted was the amount that would have fixed the problem. The quoted amount from a contractor was a little over $5k. This was agreed by the previous owner and me. I am not into pilfering society for a quick buck and I don’t work that way and never have. Attorney’s need to come back to reality and realize that this profession should be about something they love and want to do to help society as a whole; it’s not a lottery to get rich quick. I think TV and the media in the past 40 years have propagated this notion that being an attorney is the gateway to winning the lottery. What’s wrong with making only $50 to $75k a year? That’s not bad money if you live reasonably. It’s how the rest of us live.

Scott

Jul 17, 2011 10:21 AM CDT

@26: Well being a layman, yes, I did sign up for Prepaid after I knew of this problem because I did NOT have $3k. Again, “we the people” are being pushed into a wall and attorneys know this. Why do attorneys do this? Because they can. The law services used to be for the common good and for the common person on the street (think back 60+ years). Now it’s only for the rich and famous whereas the rest of us have to deal with it. As for not having the $3k? Guess what 99% of us in this country are in the same boat.

But to your point. I am not sure of why it would be an issue of signing up for a service after knowing this issue existed. I am taking advantage of a service that is cheaper and in line with my expenditures and in turn, can get me results which is value-added to me “the customer”. I researched and found a service that I can afford. This is not unethical or illegal. It’s about getting results which help me, not line an attorney’s pocket. I am self-reliant will find a way because in my profession, you need to do this. I don’t rely on policy, reg’s or some pc’ism which only delay finding root causes and getting the objective done. It’s about real work with real results. I am tired of arm-chair quarterback lawyers with ego’s explaining to me “why something can’t be done” when in fact, it is simple. “But just give me $3k, and I’ll get ‘er done!”

The legal profession has gotten this way merely because “we the people” cannot do it ourselves without a JD and passing the Bar. There is no other reason. When people ask me about my profession and what solutions could provide improvements, I do it. Do I get paid? lol. I wish. But life is about helping others when others do not have the money. Sometimes my solutions are given because what I am discussing is “shop talk”. Why can’t attorneys do this? No, they don’t have to, but then, showing compassion and respect toward the general population (who are customers) should not be like pulling teeth. In my opinion, this is why attorneys are not trusted. I have 16 years experience and a certification in my profession but I don’t ask for $3k everytime someone needs help. A friend of mine who is a retired electrician fixed my kitchen wall outlets for free last weekend. Did he charged his rate? Did he need to do it for free? He could definitely use the money. When is the last time an attorney did something for someone out of the goodness of his heart? Why can’t attorneys charge the same as everyone else? $50 an hour? $60? $75? What’s wrong with giving a freebie once in a while? How can that be unreasonable? In my profession, the fundenmentals of a good business model is about selling products and services that are value-added to the customer; charging less would increase not only your value, but the value to your customer’s and increase market share as long as you keep quality high and not undercut performance. That is how an effective business model works. To increase market share you have to charge what is value-added to the customer but without decreasing quality. But being value-added is not only about money but it is also about being customer-focused and driven to meet a customer’s expectations and goals.

Lastly, the mold issues? I researched and found products to do it myself. “We the people” don’t have the money to hire someone else. Five years later, my house is dry, mold-free, clean, and liveable.

James

Jul 17, 2011 11:05 AM CDT

Hi Scott. This is your work calling. We really need you to come in today and do your job. It’s just that we don’t be paying you today. Given your policy on “freebies” and all, we are sure you will understand and come in on your own time and work any way. Also, since your job is something you love, you should not mind doing it for free for a few days once in a while.

It is amazing to me how many people “don’t have the money” for a lawyer when they in fact DO HAVE THE MONEY. They may not want to do what it takes to GET the money, but they can get it if whey want to.

I had a situation where a guy wrote a bad check a few months ago. In my state, anything involving a bad check over $500 is a felony – fines, prison, etc. In speaking with him, he ASSURED me that he had no money. His case was turned over to the police and prosecutor. Cops show up at his house. They basically tell him they don’t want to handle the case, but will take him to jail if he does not pay in two days.

Guess what happens. The tooth fairy, Santa, Easter Bunny, whoever shows up. Dude gets the money. Maybe he had to sell something. Maybe he told his parents he was about to go to prison. Who knows. The point is that he had the money or some way to get it.

Scott, I’m glad your case worked out for you. Knowing nothing at all about you, I will still guarantee you that you could have come up with $3,000.00 to hire a lawyer if you had to. It might be unpleasant, but you CAN come up with $3,000.00. The lawyers-as-villains approach is worn and tiresome. Complaining that nobody will give you services for free (which really means they are paying your bill for you) is childish.

Hire a lawyer (or dentist or veterinarian or plumber), do it yourself, or try to get in with some prepaid thing, or barter, or marry into some guild. For MANY cases, the prepaid thing saves very little money. Sometimes it does. If it worked for you, that’s great.

Just the facts, Ma'am

Jul 17, 2011 1:39 PM CDT

So Scott, basically you cheated. Then you complain about the legal profession? The reason lawyers collect retainers up front is because of people like you who cheat. Go hang out with your fellow tradesmen or whatever you are. We don’t need no complaining cheaters here.

Show 50 more • Show all

Add a Comment

We welcome your comments, but please adhere to our comment policy. Report abuse.

Commenting has expired on this post.